It was us. We did it. We boosted the UK economy to the tune of £48 billion (cost to date of the payment protection mis-selling scandal) and that had a greater impact than the Bank of England’s quantitative easing (QE) programme according to many economists. It was a series of union surveys carried out in 2005 that resulted in the biggest financial mis-selling scandal, the sale of PPI policies, ever being exposed. Those surveys of the different sales populations found that large numbers of Lloyds sales staff: “felt pressurised to sell products to customers, which they knew they didn’t need or couldn’t afford”. At the time we said that: “The issue for Lloyds TSB is not that it happens but why it happens? We believe that the main reason is the constant, unremitting pressure to meet demanding sales targets week after week, month after month and year after year. Add to that a management culture that is dominated by ‘share of wallet’ at the expense of almost anything else and it’s not surprising we got the results we did”.

Copies of those original surveys can be found here. Lloyds desperately tried to stop the surveys being published with countless threats of retribution if we did. It’s worth noting that in 2005, PPI sales accounted for 17% of Lloyds’ profits and we were being accused by senior management of damaging the business. We published the results anyway, and the rest as they say is history. A number of national newspapers picked up the results – “Lloyds staff fear mis-selling pressure” and “If you bank at Lloyds, watch out”.

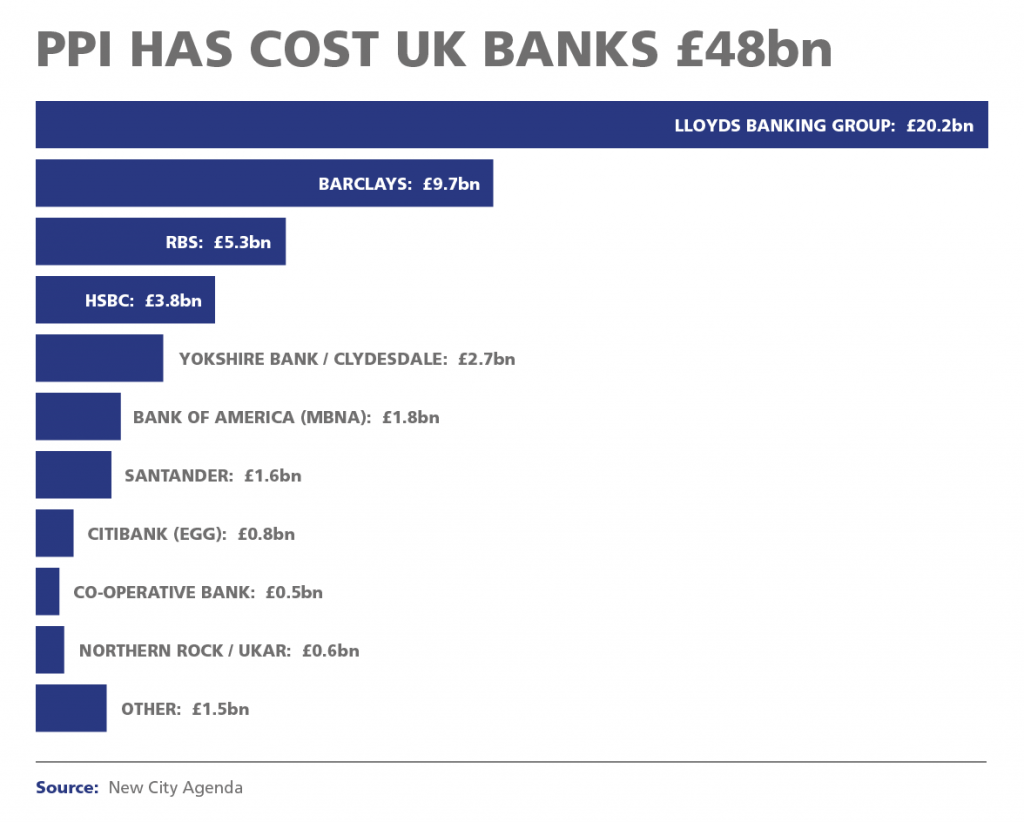

Following the outcry, the Citizens’ Advice Bureau felt so strongly about the union’s survey results that it made a so-called ‘super complaint’. It was that super complaint that resulted in new rules from the Financial Services Authority; the Competition Commission banning PPI sales at the point of sale and the resulting High Court case, which the banks lost. Lloyds was the first to admit defeat and offer compensation. Since then some £36bn has been paid out in compensation (see table below) and an estimated £12.5bn in associated administrative costs. The majority of that money has come from one organisation: Lloyds Banking Group. It initially set aside £3.2bn to deal to deal with compensation payments but that proved to be a pipe dream and the actual total is currently standing at £20.2bn. Antonio Horta-Osorio, the new Chief Executive of Lloyds Banking Group made a serious mistake in 2012 by not getting the FCA and or High Court to agree how PPI compensation would work. He left the field open to the claims companies and they have raked in massive fees at the expense of consumers.

According to Lloyds it sold approximately 16 million policies (an estimated 64 million policies were sold in the UK) since 2000. Of the policies it sold the bank says: “it has contacted, settled or provided for approximately 53% of the policies sold since 2000”. That figure will have increased but there are still lots of customers who had these products but haven’t complained.

Is History Rhyming?

The question is: could such a scandal ever happen again and has Lloyds, the worst PPI offender, really changed its sales culture? The results of the union’s latest survey of front line sales staff, which will be published in part 2 of this Newsletter, plus feedback from members shows that whilst the sales language may have changed, the focus on sales at the cost of almost everything else is still the same. It seems that 14 years on from that landmark piece of research the sales culture, which caused the PPI scandal is still alive and kicking.

In a recent interview with the Financial Times, Jonathan Davidson, director of supervision for retail and authorisations at the Financial Conduct Authority, said “When things get desperate, banks tend to take more risk. Sometimes they take more credit risk, which is why you got the financial crisis. At the same time, they typically take more of what I would call conduct risks, i.e. they take more risks in their treatment of customers. Culture doesn’t just come from the top, it comes from history”.

Of all the big banks, Lloyds is the most vulnerable to a downturn in the UK economy. A recession would increasingly put pressure on the bank to maintain income growth and that in turn could see a desperate senior management return to the bad old days. And let’s be clear, it is the senior management team at the top of the bank that would drive the culture change. Line management at the sharp end of the business will be the ones fighting against it as they were in the days of PPI.

The results of the union’s latest survey will be published in the next few days.